- Home - News

- Elections 2024

- News Archive

- Crime & Punishment

- Politics

- Regional

- Editorial

- Health

- Ghanaians Abroad

- Tabloid

- Africa

- Religion

- Photo Archives

- Press Release

General News of Wednesday, 4 June 2025

Source: www.ghanawebbers.com

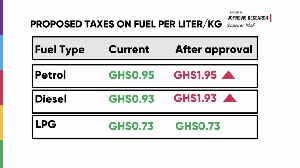

Explainer: Why petrol and diesel just got GH₵1 more expensive

In the early hours of June 4th, 2025, Ghana’s Parliament approved a GH₵1 increase to the Energy Sector Shortfall and Debt Repayment Levy on petrol and diesel.

This change raises the levy to GH₵1.95 per litre for petrol and GH₵1.93 for diesel. Liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) is not included in this increase.

The Energy Sector Levies Act (ESLA) was introduced in 2015 and implemented in 2016. It aimed to streamline energy taxes and help struggling state-owned utilities.

From January 2016 to December 2024, total collections from all ESLA levies reached GH₵27.2 billion.

In 2025, the government expects to collect GH₵9.57 billion. Data from JoyNews Research shows that GH₵2.1 billion has already been collected in the first five months of this year.

This brings total collections to over GH₵29 billion.

So why is another GH₵1 being added to fuel prices? Where did all the previous billions go?

The tax hike was not included in the 2025 budget.

In March, Finance Minister Dr. Cassiel Ato Forson assured Parliament that levies would be reviewed but not raised.

He stated plans to consolidate existing levies without increasing them.

However, less than three months later, this promise has been broken.

Falling global oil prices and a stronger cedi have lowered fuel prices significantly. This gives the government cover for the new levy without causing public outrage.

At GOIL stations, diesel costs GH₵12.98 per litre and petrol costs GH₵12.52 now, down from nearly GH₵16 earlier this year. Some private marketers are selling below GH₵12.

The Ministry of Finance believes this creates “fiscal space” for the new levy without significant consumer backlash. However, transport unions have already cut fares by 15 percent due to lower fuel prices.

The government justifies the GH₵1 increase as necessary for supporting a widening energy sector shortfall and ensuring stable power supply.

The sector’s deficit was $1.46 billion in 2024 and is projected to rise to $2.23 billion in 2025.

By March this year, total accumulated energy sector debt hit $3.1 billion.

A major issue is Ghana’s reliance on expensive liquid fuels for thermal plants. The country expects to spend $1.2 billion on these fuels this year.

These costs fall outside regulated tariffs, creating financial problems unless tariffs rise significantly—an unpopular move politically.

This raises questions about why Ghana relies on liquid fuels instead of cheaper natural gas options available at its thermal plants.

Ghana has 15 thermal plants; most can run on natural gas while eight can switch to liquid fuels when necessary due to supply issues or disruptions along pipelines like WAPCo.

If supply issues exist, clearer communication with the public is needed regarding these challenges.

Even the Finance Ministry acknowledges deeper structural problems: poor revenue collection, system losses, weak enforcement mechanisms, costly generation contracts, underperforming utilities, and misallocated subsidies contribute significantly to financial woes in the sector.

Given these known issues, why raise taxes instead of fixing systemic problems?

Private sector involvement in electricity distribution by ECG is being considered as a potential solution for these issues.

But if reforms succeed, will the new levy be removed? Or will it become permanent like many previous “temporary” taxes?

The government claims that raising this levy won’t hurt consumers because fuel prices are currently low and the cedi is strong.

However, if oil prices rise or if the cedi weakens again—the tax could negate recent consumer relief gains.

While fiscal stability motives are valid—Ghanaians deserve clarity about prioritizing liquid fuels over gas options.

Is this merely a short-term fix or part of a long-term strategy? What plans exist for reversing this tax once conditions improve?

Transparency remains essential throughout this process.

Once implemented, regular updates should inform citizens about how much revenue has been raised and how it’s spent.

Most importantly: If previous collections of GH₵29 billion didn’t solve existing problems—will one more cedi make any difference?

Entertainment